Whatever floats your moat: Tower of London’s former waterway receives help to adapt to the pressures of climate change

The former moat at the Tower of London is one of five gardens across the globe that have been selected by the World Monuments Fund (WMF) for aid in adapting to the growing pressures of climate change.

Created by Edward I in 1270 to protect the tower from attackers, the moat was an impressive 50m wide (164ft) and, filled with water flowing through from the Thames, extremely deep. Soon it was in use as a pike fishery, which continued for centuries, perhaps until the Duke of Wellington (then Constable of the Tower) had it drained in the 1840s, due to the moat’s ‘obnoxious smell’ and the ‘putrid animal and excrementitious matter’ that appeared when the tide was out, spreading disease.

Within 50 years, resourceful Londoners had repurposed the sunny south moat as a spot for growing vegetables, while livestock grazed throughout the rest. In January 1928, an extraordinarily deluge turned it back into a moat, briefly submerging the football pitch the Tower Garrison had set up; and during the Second World War, the entire moat was an official ‘Dig for Victory’ allotment. Soldiers camped in it during Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, it was decorated with 470,000 begonias for the late Queen’s Silver Jubilee and a 2022 initiative called Superbloom utilised some 20 million seeds to transform it into a wildflower meadow with meandering paths.

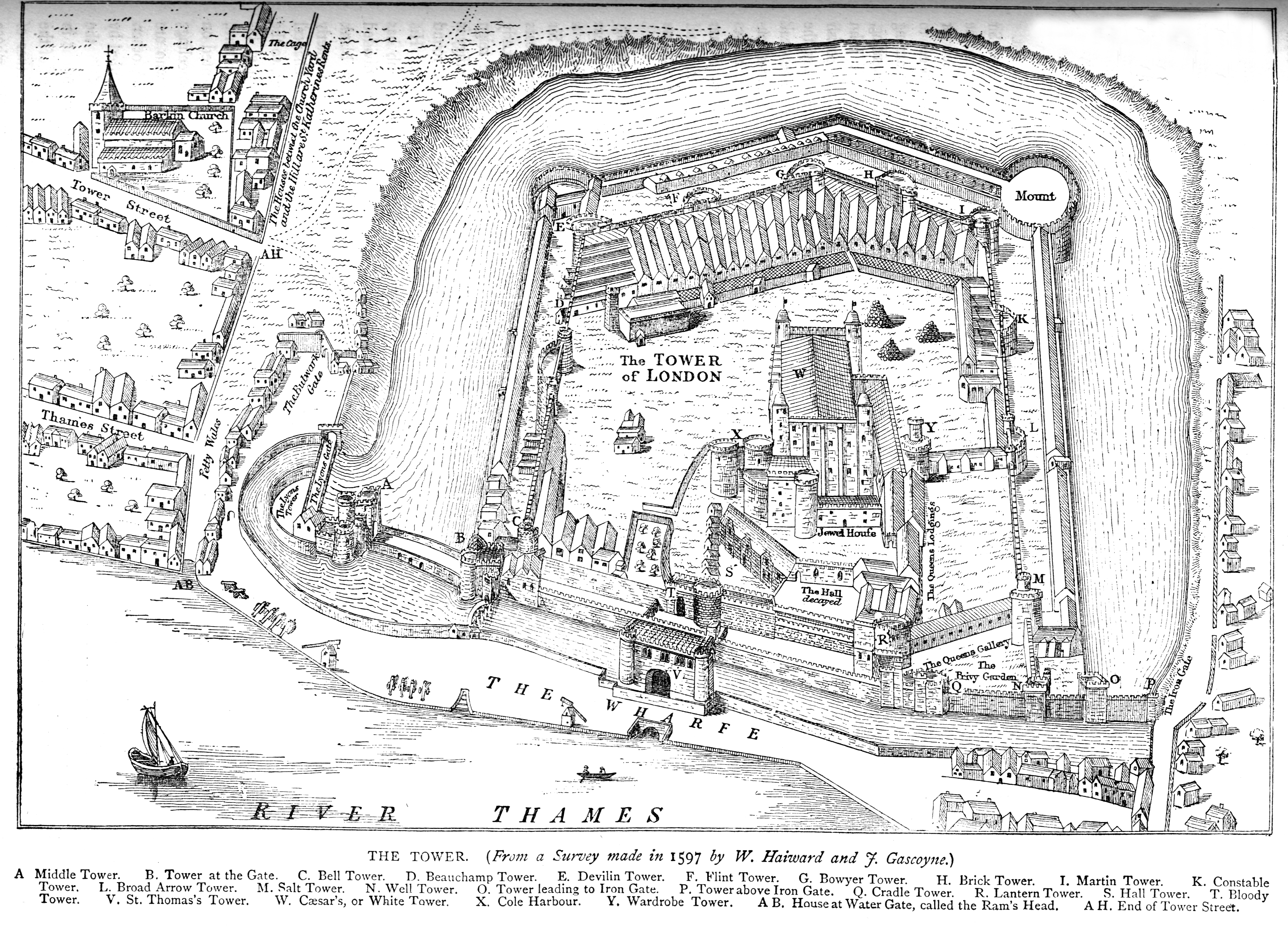

Map of the Tower Of London in the 18th and 19th centuries.

(Image credit: RockingStock/Getty Image)

The Tower of London Moat was filled with millions of wild flower seeds to encourage wildlife in 2022 as part of Superbloom.

(Image credit: Paula French/Alamy)

Now Historic Royal Palaces will work with WMF to ensure that the moat is ‘a model for sustainable greenspace by revitalising historic infrastructure to better manage water and introducing wetland landscapes to support urban biodiversity. The project will also install environmental monitoring systems and conduct biodiversity assessments to bolster the moat’s ecological resilience while deepening public appreciation of its historic and future environmental value’.

Other sites in the Cultivating Resilience initiative include the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, Nigeria, a place of worship for four centuries, the Waru Waru Agricultural Fields, high in the Lake Titicaca basin of Peru, New York’s Central Park and the Chinampas of Xochimilco, Mexico, one of the world’s oldest wetland agricultural systems.

The Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria.

(Image credit: Roert Harding/Alamy)

New York’s Central Park is a popular tourist attraction.

(Image credit: James Kirkikis/Alamy)

‘Historic gardens and managed landscapes are essential infrastructure for climate action,’ explains Meredith Wiggins, senior director of Climate Adaptation at WWF. ‘Urban parks can significantly cool neighbourhoods during heatwaves. Mature trees absorb stormwater and carbon, and traditional land management practices support food security and biodiversity. These places offer practical solutions to today’s climate challenges while connecting communities to history, nature, and one another.’

‘Climate change is one of the most urgent threats facing cultural heritage today,’ adds Bénédicte de Montlaur, WWF president and CEO. ‘By developing climate adaptation solutions at historic gardens, we are addressing this challenge head-on by investing in green heritage spaces that safeguard both ecological balance and cultural identity. This work reflects WMF’s commitment to a future where climate adaptation and cultural stewardship go hand in hand — where preserving the past helps communities prepare for what’s next.’

For further information visit the World Monuments Fund’s website.

link